I Can Do This All Day: Strategic Lessons From The Civil War

About 20 years ago this month, I started my freshman (plebe) year at West Point. And to this day I still feel and identify as a plebeian. At West Point, I majored in Military History and Environmental Engineering. Military History was really why I went to West Point. There were many things that drew me to West Point (service, leadership, independence from my family, brain and brawn, etc…) but as a high school student who loved history, I learned about the school through my study of history.

Cadet basic training really whooped my rear. I was the worst new cadet in cadet basic training, but I got better with each day. And I really enjoyed studying history at West Point. Wikipedia defines history as the “study of the past” but I like to think of history as the study of why the world is the way it is. A friend who read a draft of this essay pointed me to an excellent quote by James Baldwin:

“History, as nearly no one seems to know, is not merely something to be read. And it does not refer merely, or even principally, to the past. On the contrary, the great force of history comes from the fact that we carry it within us, are unconsciously controlled by it in many ways, and history is literally present in all that we do. It could scarcely be otherwise, since it is to history that we owe our frames of reference, our identities, and our aspirations.”

Recently I found myself re-reading the history of the American Civil War. Here are six strategic lessons from my rereading of that time period.

...

Lesson 1: Graduating from West Point Reveals Very Little about One’s Character

The place prides itself on “Duty, Honor, Country” but it’s interesting to note that some of our nation’s greatest enemies graduated from the school and perhaps one of our nation’s greatest enemies was in fact it’s superintendent: Robert E. Lee. Lee was not alone. “West Point graduates on the active list numbered 824; of these, 184 were among the officers who turned their backs on the United States and offered their swords to the Confederacy [22% on the active list violated their oaths]. Of the 900 graduates then in civil life, 114 returned to the Union Army and 99 others sought Southern commissions.” [11% who were civilians who violated their oaths] In comparison, “only 26 enlisted men are known to have violated their oaths.” Source: American Military History (Volume I), Center of Military History. This is the textbook used by ROTC cadets across the nation. It’s generally a reputable history textbook, but it has its flaws. One of the flaws of the book is its overly sympathetic and cozy depiction of the Confederate States of America.

...

Lesson 2: Success at West Point Has No Bearing to Success in the Real World

There were many cowardly West Pointers but thankfully there were some good ones too: such as Ulysses Grant (who I now think of as the Captain America of the Union Army). He wasn’t afraid to get into a fight and was renowned for his army’s ability to absorb punches. He didn’t have many superpowers, but he did have a superpower of going toe to toe with the enemy and outlasting them. President Lincoln liked him because he took the fight to the enemy, and didn’t give the Confederate/Rebel Army a break. If he lost 5,000 troops in one day and the Confederates lost just as many, then he would most likely shrug and say: “I Can Do This All Day.” This is why Grant was referred to as Unconditional Surrender. Grant wasn’t anywhere near the top of his class when he graduated but he did beat Robert E. Lee, a former superintendent of West Point. The school even has a barracks named after Lee.

To use another Marvel analogy, it almost feels like Lee and his generation of West Pointers turned leaders of the Confederacy are like Thor’s sister, Hela: the school has yet to square with just how fundamentally traitorous Lee’s actions were. Consider also this: Jefferson Davis, the grand vizier (President of the CSA) was also a West Pointer and was the Secretary of War for the United States from 1853-1857. Imagine a former Secretary of Defense joining a rebellion to overthrow the country, and you have Jefferson Davis.

...

Lesson 3: Let’s Never Forget the “Grand Old Man of the Army”

Winfield Scott served his country in the War of 1812, the Mexican-American War, and at the onset of the American Civil War. From 1812-1861: that’s 49 years of service. One day America or another culture-country will look at its history, and when it does he will be considered an American military great. It’s too bad that he’s not known as well as he should be. Interestingly, Scott developed the strategy at the onset of the war that Grant would eventually pursue and effectuate: The Anaconda Plan (apply a tight pressure to the southern states that would squeeze them economically and militarily). For those who argue that Lee was a southerner, so what else was he supposed to do but join his neighbors in rebelling? Well, Winfield Scott was also a Virginian but he chose to “Do the Right Thing.”

...

Lesson 4: Most Great Leaders Have a Great Supporting Cast

Ulysses Grant is no exception. Bucky Barnes is to Captain America as William Sherman is to Grant.

Sherman burned the south down — and while some might remember him for his march to the sea — what he really destroyed was the South’s ability to wage war effectively. If the Anaconda plan was to strangle the South economically and militarily, then what Sherman did was to suplex the south by destroying it’s rail lines. In Sherman’s own words, he was responsible for destroying up to 205 miles of railroad line in Mississippi and it was “the most complete destruction of railroads ever beheld.” Railroads in 1860 were like what the internet is in 2020. If someone was interested in waging total war today, they would take out the internet. This would of course cripple any modern country’s ability to function. Especially now that everything is in the cloud and even more so due to COVID-19. And for this reason, the present and future of war is cyber.

...

Lesson 5: Don’t Let Experience Get in Your Way

On paper, Jefferson Davis should and would have made a better leader than Lincoln. Davis was a West Pointer, fought in the Mexican-American War, and also was the Secretary of War. Davis also knew his military leaders very well and knew how to build, train, and field a fighting force. Winfield Scott never received a formal military education but “was a voracious reader who studied the great works on military science.” Scott read books, got to see theory meet reality, and didn’t let education or experience get in his way.

...

Lesson 6: It’s Not Whether You Win or Lose. It’s How You Respond.

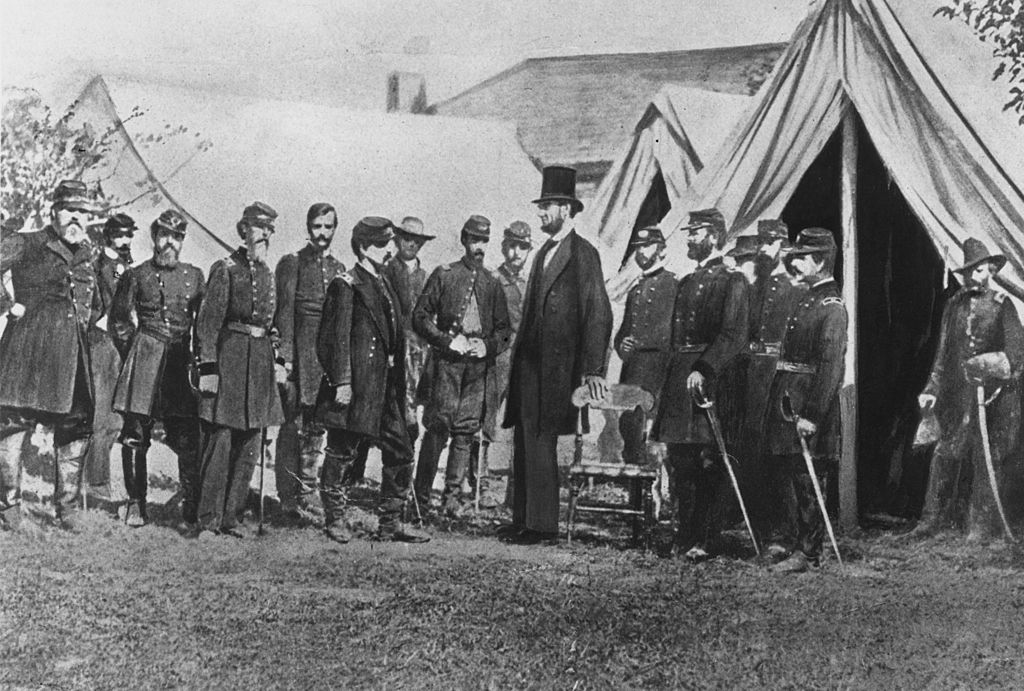

(Rischgitz via Getty Images)

Lincoln, like practically every American leader, thought that the war he was going to wage was going to be a short war. In 1861, when the war started, he didn’t think the war would last several years. Initially, his focus was on capturing the southern capital, Richmond. Gradually, he realized that the center of gravity wasn’t the Southern capital but the confederate army.

Lincoln’s military initially suffered several losses to Lee and Stonewall Jackson. But Lincoln, like Grant, always answered the bell. If the Civil War was a 12 round boxing match, then Lincoln was Rocky. He lost the first 6 rounds, tied the next 3 rounds, and won the last 3 rounds. And in the last round, he won by TKO. Lincoln’s mastery is that he survived the first 6 rounds and quickly learned to adapt to the enemy and circumstances; he was smart enough on his feet to change his strategy. Then, during the 3 rounds that he tied, he gave the North the impression that the stalemate was a victory, and that momentum was on their side. Antietam was a stalemate, but after that bloody battle (the bloodiest day in American history with 13,000 Union troops killed, wounded, or missing and 10,000 casualties on the Confederate side) he issued the Emancipation Proclamation. He turned what was militarily a stalemate into a political success. And then after the Battle of Gettysburg, which is the greatest land battle on the North American continent (43,500 casualties), Lincoln delivered the memorable Gettysburg address:

“It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us — that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion — that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain — that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom — and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

...

Lesson 7: The Lost Cause Might Have Truly Been a Lost Cause

On paper, the south seemed like it had a better leader than the Union (Davis rather than Lincoln), but the north was much wealthier and more advanced economically and industrially. The north (USA) had more railroads, more people (23 million compared to 8 million), and more soldiers (2.1 million compared to ~850,000 confederate troops).

When reflecting on this, it made me wonder and wish to easily have data that answers this question: what is the percent of wars where the economically advanced country loses (If a country or nation-state is wealthier and more economically developed, then how often do they lose the war)?

The more I think about the answer, the more I realize that yes, of course, less wealthy combatants win wars, just a quick review:

- Afghanistan and Russia (Cold War)

- Afghanistan and the USA (post 9/11)

- Vietnam and the French (post WW2)

- Vietnam and the USA (Vietnam War)

I think this question is important because material is important — but more important than material is morale. America’s military might is really just a combination of it’s moral (or morale) and it’s material (industrial and economic power).

The South could have “won” — much like the combatants in Afghanistan and Vietnam — by taking a Fabian strategy: “The Fabian strategy is a military strategy where pitched battles and frontal assaults are avoided in favor of wearing down an opponent through a war of attrition and indirection.” And the more I reflect on the brilliance of Lee and Stonewall Jackson, the more I realize that they were perhaps tactically brilliant but strategically foolish. Instead of trying to attack the Union, they should have adopted a more Fabian-like approach and tried to wear out Lincoln and Grant.

...